Skin in the Game: The Strange World of Anthropodermic Bibliopegy

I first stumbled across the term anthropodermic bibliopegy as an undergraduate English Literature major, somewhere between a late-night rabbit hole on rare books and a conversation with a professor with a taste for the macabre. The idea that a book could be bound in human skin – actual human skin – sounded like something out of a horror novel. I assumed it had to be a dark literary myth. But it turns out, it’s quite real.

Now, nearly 25 years into my career in bookbinding and conservation, I’ve handled volumes ranging from 12th-century Coptic bindings to contemporary artists’ books – but to my knowledge, I’ve never encountered one of these macabre rarities in the wild. Still, the topic has fascinated me for decades. Not so much for its shock value (though let’s be honest, that’s part of the allure), but for what it reveals about our history – medicine, justice, ethics – and the strange things humans have done in the name of preservation. These books are windows into a world of dissection tables, gallows, and lab benches, where the boundary between artifact and human remains gets uncomfortably blurred.

What is Anthropodermic Bibliopegy?

Anthropodermic bibliopegy is the formal term for the practice of binding books in human skin. It comes from Greek roots: anthropodermic meaning “human skin” and bibliopegy meaning “bookbinding.” It sounds like a campfire tale, but scattered through history are genuine volumes with these unsettling bindings quietly sitting on library shelves. While exceptionally rare, such bindings were created for a handful of reasons. Most commonly, 19th-century physicians used the skin of cadavers as grim keepsakes or “research souvenirs.” In other cases, institutions or officials bound books in criminals’ skin as a post-mortem punishment – essentially turning an executed felon into a cautionary tale in leather. Over time, the existence of human-skin books became entangled with rumor and sensationalism. But in recent years, modern science and history sleuths have begun to separate fact from fiction in one of the strangest corners of book history.

It’s worth noting that anthropodermic bibliopegy isn’t a new urban legend or something invented by horror writers. References go back at least to the 18th century – a 1700s traveler noted seeing a prayer book in Bremen purportedly bound in human leather, which he found morbidly appropriate for a text about mortality. There are even anecdotes from the French Revolution: contemporaries whispered that revolutionaries had set up a tannery in 1790s Paris to turn executed aristocrats’ skin into leather for books and boots. Most of those extreme French Revolutionary tales were likely propaganda or exaggeration, but they show that the idea of human leather was “in the air” during chaotic times. And indeed, a few early examples of human-skin bookbindings survive from the 16th–18th centuries, though they’re hard to verify. For instance, books in the libraries of French aristocrats and revolutionaries have inscriptions like reliée en peau humaine (“bound in human skin”), though only scientific testing today can tell if those claims are true.

So what kinds of books got this treatment? Surprisingly, not the occult grimoires or satanic bibles one might imagine. Instead, the confirmed cases are rather prosaic: medical texts, anatomy atlases, legal treatises, even love poetry. It appears that anthropodermic bibliopegy peaked in the 19th century, especially among medical professionals. Let’s dig into that history – and some of the unbelievable stories behind these bindings.

A Brief History: Doctors, Criminals, and Cadavers

By all accounts, the 1800s were the heyday of anthropodermic bookbinding. Far from being the work of serial killers or demented bibliophiles, many confirmed human-skin books were made or owned by upstanding physicians and scientists. In an era when the bodies of the poor and unclaimed dead were routinely used for dissection in medical schools, some doctors took a small extra liberty: preserving a piece of skin as leather for binding books. It sounds ghoulish (and it is), but within their 19th-century mindset it was almost seen as a curio or homage to their profession. As one chemistry professor involved in recent tests noted, many of these books were medical volumes bound by physicians – perhaps as a way to “honor” patients who had “contributed to medicine” by giving their bodies to science. Historian Megan Rosenbloom puts it more bluntly: back then, a “dead person’s skin had become a by-product of the dissection process,” like leftover material that a doctor might turn into a book cover for their library. (Think of a veterinarian saving the hide of an animal they dissected – except in this case the doctor and the subject were the same species.)

For example, Dr. John Stockton Hough, a young Philadelphia physician, performed an autopsy in 1869 on a woman named Mary Lynch – a poor hospital patient who died of tuberculosis and parasitic infection. Hough, an avid book collector, decided to memorialize the case by using a section of Lynch’s thigh skin to rebind three medical textbooks on human reproduction. He tanned the skin himself in the hospital’s basement (legend has it he cured it in a bedpan filled with urine, a common tanning agent). Those volumes, with their quietly nondescript covers, now reside in the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia – where librarians later confirmed the bindings are indeed human leather. Another anatomical pioneer, Dr. Joseph Leidy – a renowned 19th-century anatomy professor at the University of Pennsylvania – had his own 1861 anatomy textbook bound in the skin of a fallen Civil War soldier. Leidy had served as a Union Army surgeon, so the unfortunate “donor” was likely one of the soldiers who died under his care. In an era before modern ethics, doctors like Hough and Leidy felt entitled to use human skin as just another binding material – an extremely unusual one, to be sure, but not forbidden within their circles

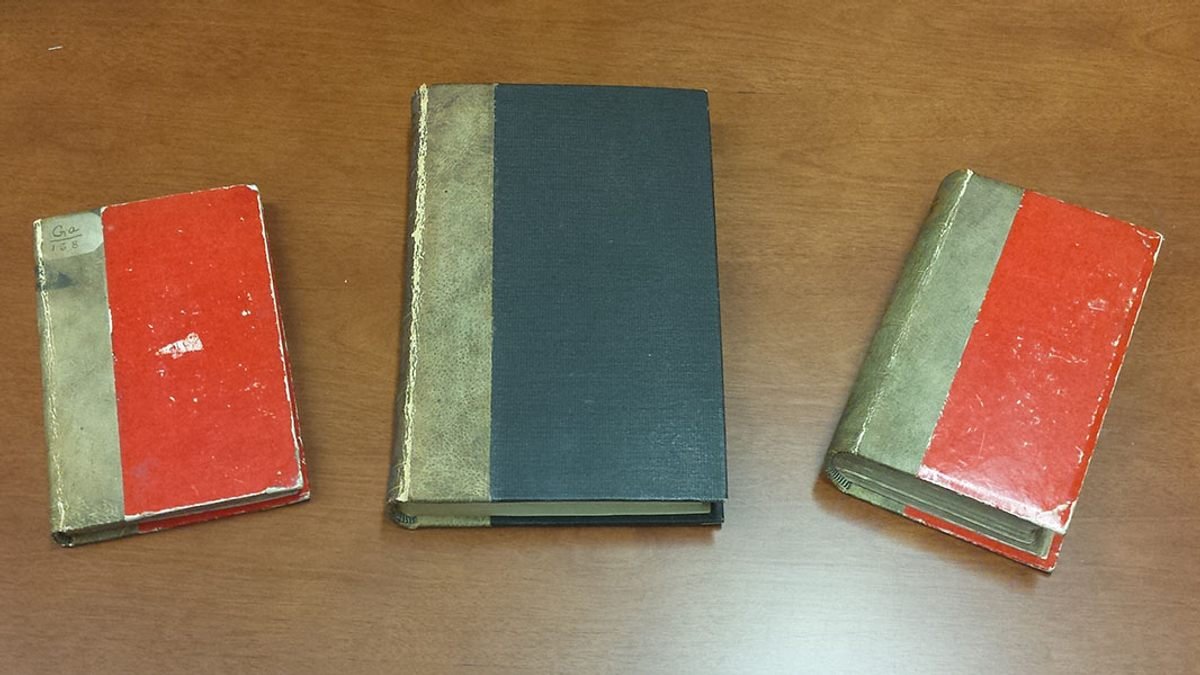

Medical books bound with the skin of Mary Lynch

It wasn’t only American physicians at this game. Over in France, a surgeon named Dr. Ludovic Bouland bound several books in skin in the mid-1800s. The most famous is a copy of a philosophical essay, Des destinées de l’âme (Destinies of the Soul), that Bouland bound in the skin of a female mental patient who had died at the hospital where he worked. Bouland left a note (rather proud in tone) explaining that he felt a book on the human soul deserved a human covering, and pointing out that you could “easily distinguish the pores” in the leather. That book ended up in Harvard’s Houghton Library in the 20th century, and for decades staff treated it as a morbid oddity – even subjecting new student employees to pranks with it – until scientific tests finally proved it was real (more on that soon).

Des destinées de l’âme (Destinies of the Soul) embodies the nineteenth-century fusion of scientific inquiry and moral philosophy - an artifact of an age that sought meaning in the corporeal remnants of its own humanity

Meanwhile, some anthropodermic books had an even more punitive origin story. In the 1800s it was not unheard of for authorities to use the skin of executed criminals to bind accounts of their crimes or other related texts. The idea was literally to make a criminal’s story skin-deep – turning their body into a warning. In 1821, for instance, the skin of John Horwood – an 18-year-old hanged at Bristol New Gaol in England – was tanned and used to cover a book documenting his trial and execution. Surgeon Richard Smith, who conducted Horwood’s post-mortem, commissioned the binding. He described the process in a lecture: Horwood’s skin was removed during dissection, tanned in an oak tub using tannins provided by local tanners, then sent off to a binder in London to be made into a cover. The dark brown leather volume, now kept at Bristol Archives, is emblazoned with a skull-and-crossbones and the Latin inscription “Cutis Vera Johannis Horwood” – meaning “the actual skin of John Horwood” – in gilt lettering. It contains notes on the murder case, Horwood’s execution, and even a sketch of the young man inside. For many years the Horwood book was treated as a gruesome relic of local history; it’s now so fragile that it’s mostly kept in storage, though a digitized version can be viewed by researchers. (Interestingly, Horwood’s remains were finally given a proper burial in 2011, nearly 190 years after he was executed – a reminder that these “objects” are also human remains deserving respect.)

Book bound in John Horwood's skin which is now on display at the M Shed, Bristol

Not every instance of human-skin binding was meant as punishment or public spectacle. Some were essentially personal mementos or scientific curiosities. Medical museums and libraries today hold a few such bindings that were created by doctors for their own collections. For example, Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum (part of the College of Physicians) owns multiple books proven to be bound in human skin – including Dr. Hough’s trio of books from Mary Lynch’s skin. These volumes are often plain-looking on the outside, giving no hint of their grisly origin except perhaps an old penciled note in the endpapers. In one case, a 17th-century anatomy text in the Mütter’s library was found to have a handwritten note stating it was bound with “the skin of Mary Lynch” – a claim later confirmed true by peptide analysis. It’s a jarring thought: an object can sit quietly on a shelf for centuries, harboring a horrific secret in its binding that only modern science can uncover.

The Highwayman Who Gifted His Skin

Among all anthropodermic books, perhaps the most infamous (and oddly touching?) story is that of James Allen, a 19th-century highwayman in Massachusetts. Allen – also known by the alias George Walton – was a convicted robber who, while in prison, wrote a memoir/confession titled Narrative of the Life of James Allen. Upon his death in 1837, Allen made a bizarre last request: that a copy of his life story be bound in his own skin and given to the one man who had ever resisted him during a robbery. In a strange twist of criminal chivalry, Allen essentially volunteered his skin as binding material for this special presentation copy.

That man, John Fenno, indeed received this morbid gift – a slim volume bound in the tanned skin of the very criminal who once tried (and failed) to rob him. It remains one of the only known anthropodermic books made with the consent of its source. Allen’s body was used in an almost respectful way, by his own design – a posthumous act of contrition and commemoration. According to later tellings, Fenno’s family kept Allen’s memoir on their bookshelf and supposedly even used it to discipline misbehaving children (one can imagine a stern Victorian parent intoning, “Behave, or I’ll fetch the skin book!”). Dark humor aside, the Allen volume – now held at the Boston Athenæum – has been scientifically tested and confirmed to be human skin. This gruesome keepsake gives new meaning to the phrase “bound by fate.” It’s a one-of-a-kind blend of penitence and bravado: Allen literally left a piece of himself behind to ensure his story would not be forgotten.

The James Allen volume remains the only documented example of anthropodermic binding performed with the source’s consent. Before its bequest to the Boston Athenæum, it reportedly remained in the Fenno household, where it served as a disciplinary implement—a macabre extension of its moral lesson

Myths, Rumors, and the (Lack of) Nazi Connection

Whenever people hear about books bound in human skin, their minds often leap to the most sensational scenarios – Nazi atrocities, deranged serial killers like Ed Gein, or satanic cult spellbooks bound in victims’ flesh. In reality, these are largely myths. Despite the ubiquity of such tropes in horror fiction, there is no solid evidence that the Nazis had a systematic practice of binding books in Holocaust victims’ skin, nor that any known serial killer made a human-skin book. (Notorious murderer Ed Gein did craft gruesome items from human skin in the 1950s – lampshades, belts, and such – but books were not among his creations.) The confirmed anthropodermic books overwhelmingly trace back to the 17th–19th centuries, tied to medical professionals and occasional judicial punishments – not to madmen in basement lairs or modern war criminals.

That said, human-skin books have inspired rumors for ages, and not all of them are entirely baseless. During the French Revolution, as mentioned, there were whispers of human leather being used for various patriotic (or depraved) purposes. In the 19th century, some books surfaced with claims to be bound in the skin of exotic or marginalized individuals, often with a sensational or even racist spin. A notorious example: a small book in the late 1800s purported to be bound in the skin of Crispus Attucks – an African American man famed as the first martyr of the American Revolution. The cover’s inscription brazenly bragged that it was made from “the skin of the Negro whose Execution caused the War of Independence.” Suspicious? Absolutely. And indeed, when scientists in modern times examined it, they found with 99% certainty that the binding is actually goatskin, exposing the claim as a shameless fake. In general, any historical book that loudly advertises its human-skin origin – especially with a salacious story – should be taken with a heap of salt (and ideally, a protein analysis). As one expert wryly noted, books that “call attention to the race of the skin” used are usually frauds. The real anthropodermic bindings were usually far more discreet, often discovered only through hidden notes or scientific testing rather than gaudy inscriptions.

Interestingly, there is one confirmed modern exception to the “no Nazis” rule. In 2020, researchers at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum in Poland revealed that a Nazi-era photo album in their collection is very likely bound in human skin. Using a different analytical technique (Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy), they identified human skin in the album’s binding. This artifact – apparently made by an SS officer at the Buchenwald camp – is a chilling outlier. It appears to be a singular case and not evidence of a widespread Nazi practice, but it shows that the idea did occur at least once in that horrific context. Generally, though, the stereotypes of anthropodermic bibliopegy (Nazi grimoires, occultist tomes, etc.) are far less common than the prosaic reality: doctors, libraries, and collectors quietly passing down morbid mementos of medical history.

The Science of Identifying Human Skin Books

For a long time, determining whether a book was truly bound in human skin was mostly guesswork and lore. Librarians and collectors relied on visual inspection – for instance, examining the pores in the leather under magnification, hoping to distinguish the follicle patterns of human skin versus pig or calf. Such methods were imprecise and often wishful thinking. In the early 2000s, some attempted DNA testing on suspect bindings, but that turned out to be problematic: old books pass through many hands, and human DNA from centuries of handling can contaminate the surface, yielding false positives. Moreover, the tanning process and sheer age of the leather often degrade DNA to the point of uselessness. When you tan a hide – using chemicals, salts, even urine – you essentially cook and preserve the collagen but likely destroy most DNA in the process. As chemist Richard Hark quipped, after that treatment “you’re not likely to find a lot of usable DNA” left in a 150-year-old binding.

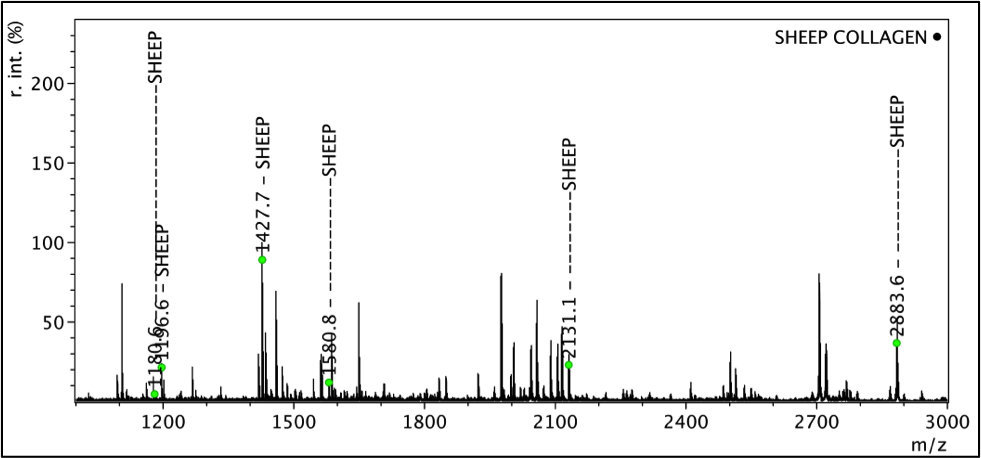

Enter the Anthropodermic Book Project (link): a team of scientists, librarians, and museum curators who set out in the mid-2010s to apply modern chemistry to this morbid mystery. Starting around 2014, the project popularized an inexpensive and nearly non-destructive test called peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF) to identify the animal origin of bookbinding leather. In a nutshell, PMF analyzes collagen, the structural protein in skin (and in leather). Every mammal species has slightly different collagen peptides – a unique protein “fingerprint” – which can be detected with mass spectrometry. The process works like this: researchers take an extremely tiny sample from the book’s binding – usually a sliver or shaving no bigger than a speck of dust (if you can see it with the naked eye, it’s more than enough). They digest this minuscule sample with an enzyme, which breaks the collagen into short peptide fragments. Then they run these fragments through a MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer, which measures the mass of each peptide. The resulting pattern of peptide masses is compared against known profiles for various animals. If the peptides match those of cows, or pigs, or goats, etc., you know it’s ordinary leather. If they match the profile for primate collagen (the great ape family), then you very likely have a human skin book. (Technically, PMF might not distinguish human from, say, gorilla with 100% certainty – but let’s be real, it’s exceedingly unlikely that anyone was binding books in gorilla or orangutan hide in 19th-century Philadelphia.)

This PMF technique has proven to be a game-changer. It’s highly sensitive – collagen peptides stick around even when DNA is long gone, and tanning or aging doesn’t erase the species-specific markers. It’s also minimally invasive; librarians don’t have to destroy the binding, just scrape an almost invisible sample. Since the mid-2010s, PMF has been considered the gold standard for identifying anthropodermic bindings. As Megan Rosenbloom notes, this science finally allowed libraries to answer conclusively questions that had lingered for centuries.

Sheep vs human collagen as shown via PMF

The results have been illuminating – and a bit surprising. As of the latest count, the Anthropodermic Book Project and partner labs have tested over 30 alleged human-skin books worldwide, of which about 18 have been confirmed as human and the rest proven to be animal leather (false alarms). In other words, roughly half of the books long rumored to be bound in human skin turned out to be genuine, and half were just goats or calves in grim disguise. One early triumph of this science came in 2014, when Harvard’s Houghton Library tested its copy of Des destinées de l’âme – the book we met earlier with Bouland’s note – and got a positive identification for human skin. This confirmation made headlines (understandably). Harvard gleefully announced it on their blog at the time, even joking about “good news for fans of anthropodermic bibliopegy, bibliomaniacs and cannibals alike” – a quip they later regretted, as we’ll see. Since then, “Book Team Six” (as the Anthropodermic Book Project team playfully calls itself in media) has built a growing census of anthropodermic books across libraries and museums. They’ve tested everything from anatomy texts to an erotic novel. (Yes, even a BDSM-themed 19th-century poetry book was confirmed to have a human skin cover, a finding that raised eyebrows because many assumed such tales were just salacious fiction.) By bringing scientific rigor to what was once purely the realm of bibliographic lore, the team has unmasked old rumors and given libraries a factual basis to finally confront these objects.

Interestingly, the testing has also debunked some dramatic stories. Recall that Harvard law book with the gruesome inscription about a friend flayed in Africa in 1632? PMF revealed that cover to be sheepskin. Likewise, many books with flamboyant claims turned out to be ordinary leather upon analysis – reinforcing the pattern that the real human-skin books often had relatively pedestrian origins (medical textbooks, etc.), whereas the ones with the wildest legends often aren’t human at all. On the flip side, the testing has also uncovered a few surprises, like the rather innocuous-looking copy of an 1891 French novel with lesbian themes (Mademoiselle Giraud, My Wife) at Brown University that turned out to be human-bound. In each case, science is replacing speculation with data, one book at a time.

“Dark Archives” – The Ethical Reckoning

With renewed attention on these books has come a wave of ethical and philosophical questions. After all, a book bound in human skin is, when you get down to it, a human remain. How should we treat such objects today? Enter Megan Rosenbloom, a medical librarian and researcher who has become one of the leading voices on this topic. Rosenbloom is a founding member of the Anthropodermic Book Project team and author of Dark Archives: A Librarian’s Investigation into the Science and History of Books Bound in Human Skin (2020). In Dark Archives, she delves into the history and provenance of these books, busts myths, and grapples with their cultural and moral implications. One of the book’s key insights is how closely anthropodermic bibliopegy is tied to the history of medicine and its evolving ethics. Most confirmed skin-bound books were created by medical men in an era when consent and dignity for the dead were often ignored. Rosenbloom draws a line from these objects to broader issues in medical ethics – reminding us that not so long ago, even respected doctors felt entitled to use unclaimed bodies (often those of the poor, marginalized, or institutionalized) for whatever purposes they saw fit. In the 19th century, it was common for medical schools to dissect paupers’ bodies without family consent, and to keep souvenirs like skulls, skeletons, or in these cases, skin bindings. These books, she argues, force us to confront that troubling legacy of exploitation in the name of science. As Rosenbloom puts it, the body was literally viewed as a commodity in service of knowledge or punishment – skin could be “harvested” like any material, an attitude that today is abhorrent but back then was within the norms of anatomical science.

Rosenbloom, who is part of the “death-positive” movement (which advocates for open, respectful engagement with death and human remains), approaches these books with a mix of curiosity and respect. She generally supports preserving them as historical artifacts – arguing that to destroy or hide them would be to lose the important lessons they carry. However, she’s well aware that they are “ethically fraught” objects. In fact, that exact phrase – “ethically fraught” – was used by Harvard University in 2024, when it made a landmark decision regarding its infamous human-skin book. In March 2024, Harvard announced it had removed the human leather binding from Des destinées de l’âme – the very book they had confirmed a decade earlier. The cover, which had been intact since the 1880s, was carefully taken off and placed into secure storage. Harvard’s library leadership explained that after much deliberation, they concluded that such human remains “no longer belong in the library collections” because of the lack of consent and the problematic origins of the book. They are now working to research the identity of the woman whose skin was used, and to determine a final respectful disposition for the skin – possibly burial or repatriation, in consultation with ethicists and authorities.

This move by Harvard – essentially disbinding a book to remove its anthropodermic cover – stirred debate in the library and museum world. On one hand, it’s an effort to restore dignity to the individual behind the binding, acknowledging that what was once treated as a curiosity is actually the literal remains of a person who had no say in the matter. On the other hand, some historians and librarians worry it sets a precedent for destroying or hiding artifacts; after all, the binding is now out of public view, arguably a loss to research and the historical record. Harvard’s decision came as part of a broader review of human remains in the university’s collections, spurred by growing outcry over museums holding everything from Indigenous ancestors’ bones to anatomical specimens without clear provenance. In a formal Q&A, Harvard librarians even apologized for how the skin book had been handled in the past – noting, for example, that their 2014 blog posts about it were in poor taste and that student workers had once been hazed with it. They acknowledged that those actions “objectified and compromised the dignity of the human being whose skin was used” and stated that they had “fallen short of an ethic of care” in stewardship of the item. It’s a remarkable about-face. What began (even in 2014) as a kind of macabre PR stunt for the library – “look, we have a skin book!” – has turned into an exercise in humility and contrition. The pendulum is swinging from morbid fascination to humanizing and honoring the dead.

So where does that leave anthropodermic bibliopegy today? As of 2024, the Anthropodermic Book Project has paused its active testing after verifying 18 human-skin books worldwide. But plenty of alleged examples remain untested in libraries around the globe – each old volume a potential time bomb of controversy. Different institutions are handling these books in different ways. Some libraries keep them quietly in climate-controlled vaults, available only to serious researchers. Others do display them (tastefully) with proper context about medical history and a clear acknowledgment of what they are – often with a “viewer discretion” sign for the squeamish. A few, like Harvard, have now been disbound in the name of ethics, separating the human remains from the book’s text. There’s even ongoing discussion about whether descendants or communities connected to the sources of the skin (if any can be identified) should be notified or involved in decisions – a tricky proposition, since most of these books came from unnamed 19th-century bodies. In the United States, laws like NAGPRA (which require repatriation of Native American remains) don’t cover these cases since they’re not Indigenous remains. But the spirit of such policies – to treat human remains with respect and consult communities – is influencing how libraries act.

In Dark Archives, Rosenbloom recounts her travels to see various anthropodermic books firsthand. In one chapter, she describes walking into a grand library reading room with an infamous skin-bound book in her bag, only to have airport-style security swab the bag and raise eyebrows (one can imagine the explanation: “Yes, that’s a book covered in human leather, I promise it’s for research”). These sometimes comic episodes underscore how the conversation around these books is changing. Not long ago, they were primarily treated as shocking curiosities – good for a shudder or a morbid joke. Now, they’re prompting serious reflection about consent, memorialization, and the treatment of human remains in cultural collections. The tone has shifted from “Can you believe this book is covered in people?” to “What responsibilities do we have toward the person whose skin covers this book?”

Conclusion: The Legacy of Human Skin Books

Anthropodermic bibliopegy sits at a bizarre intersection of bibliophilia, medical history, and morbid curiosity. These books are physical embodiments – quite literally – of bygone attitudes toward the human body. They carry the DNA (or at least the collagen) of nameless patients, executed felons, and one overly accommodating highwayman. They are undeniably creepy, yet they have undeniable scholarly value: they tell us about the past, about how doctors once crossed ethical lines in the name of science, or how authorities sought to turn criminals into morbid legends. At the same time, they force us to confront discomforting questions in the present about consent and how we display human remains.

For anyone interested in the oddities of book history, anthropodermic books are a goldmine of strange-but-true tales – each cover hides a human story (quite literally under the surface). The initial reaction they provoke is usually shock and disbelief (“Wait, that really happened? People made books out of people?!”). There’s often a nervous chuckle at the dark irony of it all. Who could imagine a sentence like “Please bind my memoir in my skin and gift it to my friend” being a real part of history? Or librarians happily testing a book to confirm if it’s bound in human leather, and then oddly celebrating when it is? Yet here we are, with verified cases and published research to prove it.

In exploring these stories, we can approach the subject with a bit of wit and wonder – the history is nothing if not darkly fascinating – but always with an undertone of respect for the very real human material involved. These objects are simultaneously books and bodies, jokes and tragedies. They remind us that truth is often stranger than fiction, and that the written word isn’t always confined to the ink on the pages – sometimes the very binding has a tale to tell.

Next time you run your hands over a vintage leather-bound book, you might (fleetingly) wonder: what kind of leather is this? Don’t worry – the odds are overwhelmingly in favor of goat, sheep, or calf. Human-skin books were always exceedingly rare and are even rarer now. But the fact that the question can even be asked – and now, thanks to modern science, definitively answered – adds a new layer of intrigue to wandering the stacks of an old library. And as for those verified anthropodermic books that do exist, they compel us to remember that libraries and museums are full of stories – sometimes on the inside and outside of the book. They also serve as a cautionary tale: a reminder to future generations about the importance of ethical standards in both medicine and curation. In our pursuit to conquer knowledge or preserve history, we must be mindful of the human cost – lest someone ends up, quite literally, as one for the books.

Further Reading & Resources:

The Anthropodermic Book Project – Official research site tracking books bound in human skin, their scientific testing, and results. Contains FAQs and updates from the team that pioneered modern identification of these bindings. https://anthropodermicbooks.org/

Rosenbloom, Megan (2020). Dark Archives: A Librarian’s Investigation into the Science and History of Books Bound in Human Skin. A deep dive into the history, science, and ethics of anthropodermic bibliopegy, with firsthand accounts of investigating these books. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/a-look-at-anthropodermic-bibliopegy-on-megan-rosenblooms-dark-archives/

Harvard Library Statement on Des destinées de l’âme (March 2024). Harvard’s official announcement about removing a human-skin book cover, detailing the book’s history, the decision process, and an apology for past handling. https://library.harvard.edu/about/news/2024-03-27/statement-des-destinees-de-lame-and-its-stewardship

Smithsonian Magazine – “A Book Bound With Human Skin Spent 90 Years in Harvard’s Library. Now, the Binding Has Been Removed” (Sarah Kuta, April 16, 2024). A news article on Harvard’s removal of the skin cover, with historical context and expert comments. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/a-book-bound-with-human-skin-spent-90-years-in-harvards-library-now-the-binding-has-been-removed-180984057/

BBC News – “The macabre world of books bound in human skin” (June 20, 2014). Feature article discussing various confirmed and rumored examples, from the James Allen confession and John Horwood’s trial book to the Suriname Legend and more. https://www.historynewsnetwork.org/article/the-macabre-world-of-books-bound-in-human-skin

Lapham’s Quarterly – “A Book by Its Cover” (Megan Rosenbloom, 2019). Essay by Rosenbloom recounting the history of anthropodermic books, including the French Revolution rumors, the Burke and Hare case, and scientific testing outcomes. https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/book-its-cover

Wikipedia: “List of books bound in human skin.” – A referenced list of many known and alleged anthropodermic books around the world (for the truly curious). Contains up-to-date testing results as of 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthropodermic_bibliopegy